Writing alternate history means you end up doing a lot of actual historical research, if only to find good stuff to riff on. Sometimes that means researching ancient Native American cities, or the history of shanghai tunnels in Portland and Seattle.

Sometimes it means discovering New York City once had a thriving pneumatic postal system.

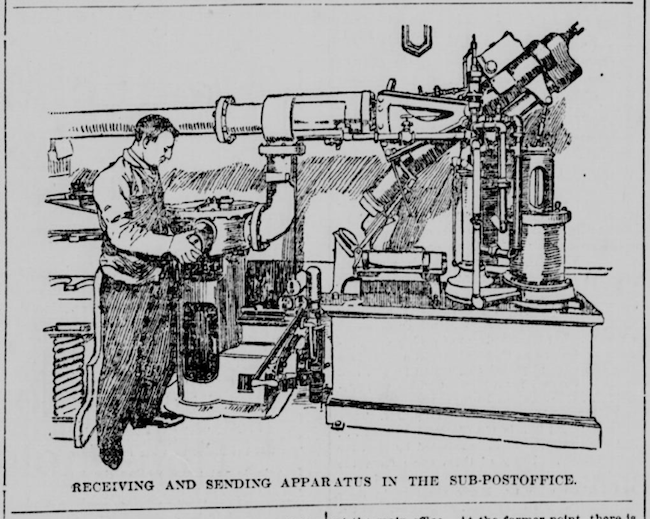

It’s true. From 1897 to 1953, a series of tubes ran up both sides of Manhattan around Central Park, about four to six feet under New York City’s streets. The line began just south of Times Square, running east to Grand Central Station, up to Triborough in East Harlem, across to Manhattanville, and down through the Planetarium Post Office near the Museum of Natural History and back to Times Square. Another triangle-shaped line ran south from Times Square and Grand Central Station all the way to City Hall in Lower Manhattan, with a spur that actually crossed the Brooklyn Bridge and delivered cylinders full of mail to the Brooklyn General Post Office (now Cadman Plaza). At its peak, the New York Pneumatic Post covered twenty-seven miles and connected twenty-three post offices throughout the city. According to legend, the system once even extended into the Bronx, where a renowned deli supposedly sent subways (ha) to postal workers at downtown post office branches.

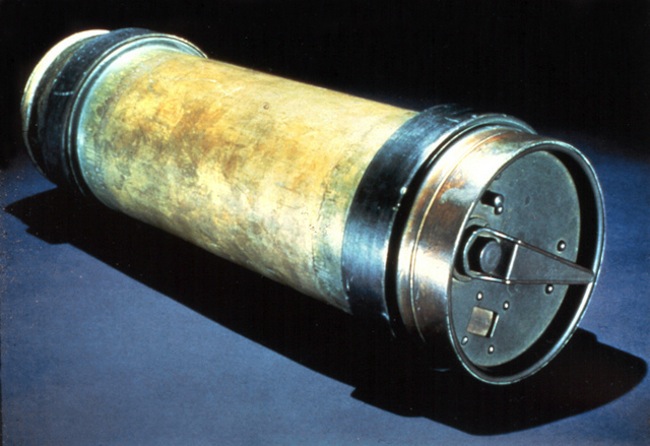

The postal workers could “eat fresh” because of the pneumatic system’s amazing speeds. The system operators were called “Rocketeers,” and with good reason: the system’s “positive rotary blowers” and “reciprocating air compressors,” first driven by steam and later by electricity, could fire its 25-pound, 21 inch long by 7 inch wide steel cylinders at speeds of up to 100 miles per hour—though due to the system’s twists and turns, canister speed was limited to 35 miles per hour. That was still pretty darn fast for turn of the century New York. It took just fifteen minutes for cylinders to go from Herald Square, well south of Central Park, to the two northernmost stations on the line. Mail was delivered from City Hall in Lower Manhattan to the General Post Office in Brooklyn in just four minutes’ time. Forty-minute mail wagon routes were reportedly cut down to seven minute trips by pneumatic post. It was, metaphorically speaking, New York’s first Internet.

And like the early Internet, New York’s Pneumatic Post quickly grew from technological novelty to heavily-used network. In its heyday, the New York Pneumatic Post carried around 95,000 letters a day—about 30% of New York City’s daily mail delivery. Each canister could hold up to 600 letters, and they were big enough to carry second-, third-, and fourth-class items like clothing and books.

The pneumatic post’s inaugural cargo, in fact, was an odd assortment of items. During a ceremonial inauguration in 1897, postal supervisor Howard Wallace Connelly and a hundred or so Post Office employees and politicians were on hand to receive the first cylinder at City Hall. Inside was something of a time-capsule of turn-of-the-century Americana: a bible wrapped in an American flag, a copy of the Constitution, a copy of President McKinley’s inauguration speech, and several other official documents. Subsequent tomfoolery between the stations saw the delivery of a bouquet of violets, a suit of clothes, a candlestick, and an artificial peach (a reference to an attending senator’s nickname). But most notorious of all was the delivery of a live black cat.

“How it could live after being shot at terrific speed from Station P in the Produce Exchange Building, making several turns before reaching Broadway and Park Row, I cannot conceive, but it did,” Connelly said years later in his autobiography. “It seemed to be dazed for a minute or two, but started to run and was quickly secured and placed in a basket that had been provided for that purpose.”

Henceforth, New York’s Pneumatic Post was sometimes referred to as the US Post Office’s “Cat Subway.”

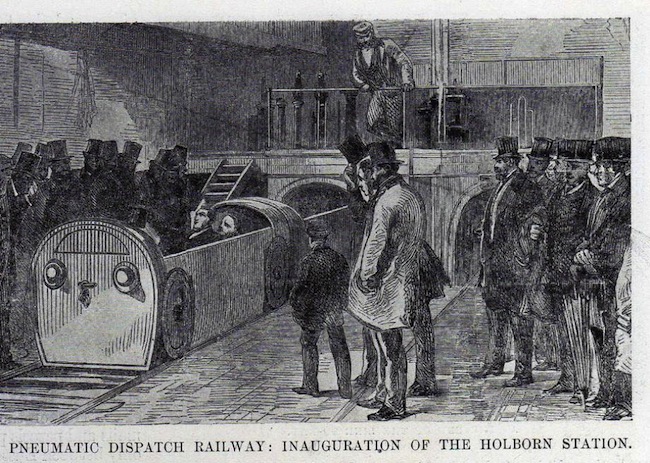

The cat wasn’t the last live passenger of New York’s pneumatic post either. While London’s Pneumatic Despatch Company, built almost 40 years earlier, was intended to just transport parcels, its coffin-sized wheeled cars were big enough to carry people—and did, when the Duke of Buckingham and a few other jokers from the company’s board of directors took a ride inside the carriages to celebrate the opening of a new station in 1865—New York’s pneumatic post was only big enough for small- to medium-sized animals, which postal employees seemed to delight in firing through the tubes. The post office reportedly sent dogs, mice, guinea pigs, roosters, and monkeys from station to station via pneumatic cylinder, once even delivering a glass globe of water and a live goldfish through the tubes without incident. At least one animal was sent through the pneumatic tubes for more noble reasons: according to one story, the owner of a sick cat was able to successfully rush his pet to an animal hospital via the pneumatic system—though whether or not the cat was sicker upon arrival than when it departed is certainly a valid question.

By 1916, Congress was authorizing federal funds to construct or expand pneumatic postal networks in major cities across the country. New York, Boston, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Chicago all had, collectively, more than a hundred miles of pneumatic tube systems carrying mail beneath their city streets and sidewalks. From there, it isn’t hard to imagine a national public works project to connect those independent systems into a single, cross-country pneumatic postal system, shooting parcels and letters from city to city in subterranean tubes at a hundred miles per hour via steam-powered air compressors. The very idea set my steampunk goggles all aquiver.

Which is why I had to put a greatly expanded New York Pneumatic Post in my middle grade alternate history fantasy novel, The League of Seven, from Tor/Starscape. In The League of Seven, a pneumatic post stretches from coast to coast, linking the “United Nations of America”—the expansion of the Iroquois League into a circa 1875 United States-sized country—to the independent nations of Pawnee, Wichita, Cheyenne, Texas, and California, and more to the West. Like the London Pneumatic Despatch, some of the Inter-net’s “p-mail” cylinders are big enough for my main characters to fit inside—which of course they do. There are hackers in this world too—criminals who hang out in the tunnels beneath major cities and literally hack into the pneumatic tubes to intercept cylinders, steal people’s mail, and send spammy Nigerian prince letters to people’s home p-mail tubes.

Which is why I had to put a greatly expanded New York Pneumatic Post in my middle grade alternate history fantasy novel, The League of Seven, from Tor/Starscape. In The League of Seven, a pneumatic post stretches from coast to coast, linking the “United Nations of America”—the expansion of the Iroquois League into a circa 1875 United States-sized country—to the independent nations of Pawnee, Wichita, Cheyenne, Texas, and California, and more to the West. Like the London Pneumatic Despatch, some of the Inter-net’s “p-mail” cylinders are big enough for my main characters to fit inside—which of course they do. There are hackers in this world too—criminals who hang out in the tunnels beneath major cities and literally hack into the pneumatic tubes to intercept cylinders, steal people’s mail, and send spammy Nigerian prince letters to people’s home p-mail tubes.

And yes, I even manage to get a “series of tubes” joke in there too.

Alan Gratz is the author of a number of middle grade and young adult novels, including Samurai Shortstop and Prisoner B-3087. To learn more about the steampunky middle grade goodness that is his new book, The League of Seven, visit www.septemberistsociety.com.

Whenever I saw this in movies, I assumed it was just something within that building. I had no idea that it covered so much ground.

Also, I owe an apology to Mark Hodder for thinking he had a quaint but impractical idea in his Burton and Swinburne novels.

I remember when the pnuematic tubes in the Government Building where I worked was replaced with Robot Carts in the 1980’s. I also remember the first arrest from using the robots to deliver drugs. lol

Actually, a lot of major cities in Europe and the US had pneumatic postal systems… the first was established in London in the 1850s. The one in Prague was still active until the flood in 2002.

The pipes that used to carry sheets of copy written by journalists still run right over my head in the newspaper office I am sitting in right at this moment.

Sterling Library at Yale, built in the early 1930s, still had a functioning pneumatic tube system in the stacks when I was there in the late 1970s. It was used to send requests from the front desk to librarians on the upper floors. I don’t know if it’s still in operation.

Didn’t Heinlein use a pneumatic system in Gulf?

Pneumatic tube systems are still used in hospitals such as Stanford http://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2010/01/gone-with-the-wind-tubes-are-whisking-samples-across-hospital.html

Pneumatic tube systems are awesome! New York also tried a pneumatic subway system, though it never went far.

The pedant in me wants to point out that while Portland had “Shanghai tunnels,” what Seattle has is a series of abandoned, interlinking rooms left behind when the streets were elevated after the Great Seattle Fire. Apparently the city decided a massive fire was a great time to rebuild in brick and make the roads higher. If you can wander around in a bunch of basements downtown, you can find doors that lead nowhere, or to places you probably shouldn’t enter without a team of engineers.

@7 A bank in my town uses a pneumatic tube at one of its drive-throughs. The bank actually has two drive-through lanes, one lane next to the building, with a conventional window and teller, and one lane with a tube system. You drive up, slide open the compartment, place your deposit-slip or check in the canister, close the compartment and press the button. You can watch the canister whoosh up through the clear plexiglass tube into the building, and then wait for it to return with the receipt or money.

@6: yes, but it was only for small items — although it apparently had massive internal switching, such that there were tens of thousands of stations all reachable from each other.

Most of the Home Depot stores I’ve been in have pneumatic systems connecting the pay stations to place back-of-house location, but they’re clearly one-way (the station tubes are ganged at several reverse-manifolds); I haven’t seen one used in some time, so they may be obsolete.

Albany Hostpital (Western Australia) opened early in 2014 has a pnuemantic system.

I see hem in use at BJs, Costco (going from the cash registers to the customer service/managers office), the local Wallgreens, and Wells Fargo bank (going from the second drive-through lane to the teller behind the window).

Interestingly, New York’s first subway was also pneumatic. A tunnel, essentially only a city-block long ,was dug in secrecy beneath Manhattan by Alfred Beach. Its construction was approved by the city as a pneumatic postal system, but later when no one was paying attention, the dimensions were enlarged so that it was capable of carrying passengers. It opened in 1870 as a demonstration of a pneumatic railway and ran for almost three years, mainly as a curiosity, while he tried to gain approval for expansion. When Beach ran afoul of New York’s kingmaker, Boss Tweed, he eventually went bankrupt and the system died. (It is mentioned in the movie “Ghostbusters II” though!)